By Brett Daniels

“And you may find yourself behind the wheel of a large automobile,

And you may find yourself in a beautiful house, with a beautiful wife,

And you may ask yourself, “Well, how did I get here?”

-Once In a Lifetime, Talking Heads

There are a lot of college football fans asking, “How did we get here?” as the sport continues to change at a rapid pace. North Carolina head coach Mack Brown remarked that due to Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL) that college football “was the mini-NFL” and that “amateurism is gone.” Brown also stated that the sport had changed more in the last three years than in his previous 47 years of coaching. Other coaches have remarked that the current model is unsustainable. To understand where it all started to change, you have to go back to a landmark lawsuit that went all the way to the Supreme Court in 1984.

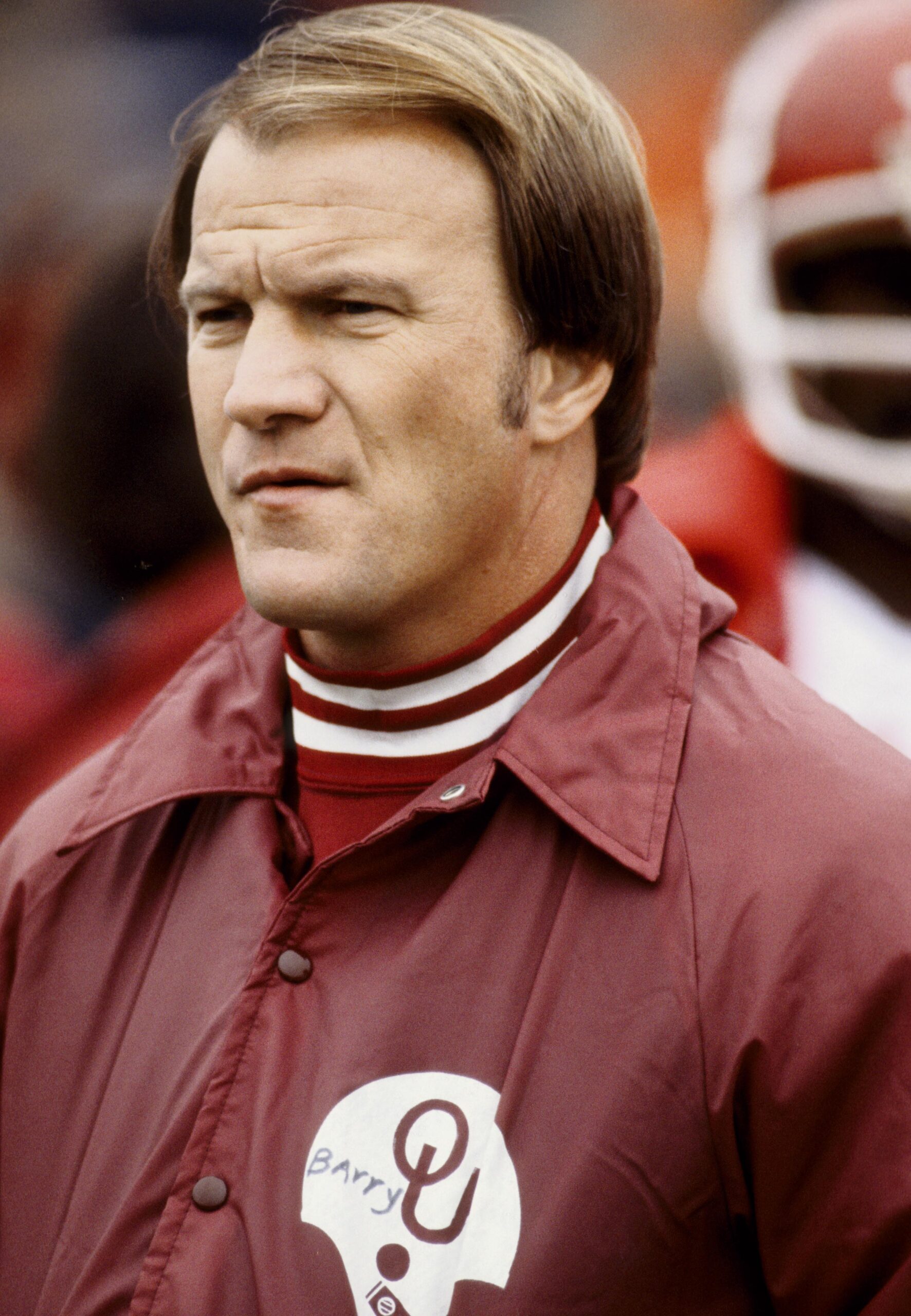

University of Georgia/University of Oklahoma v the NCAA

In 1981 the Board of Regents for the University of Oklahoma and the Athletic Association of the University of Georgia sued the NCAA over television rights. The NCAA at the time controlled the number of times each team could appear on television during the season. They claimed that by limiting televised games they were protecting live attendance at the games. The schools themselves disputed this and formed the College Football Association to negotiate television rights with the networks. After being informed that the member schools would be ineligible for any NCAA championships, Oklahoma and Georgia filed suit. The case was adjudicated in 1984 when the Supreme Court ruled that the NCAA had violated both the Sherman Antitrust Act and Clayton Antitrust Act. As a result of this ruling, all the member schools now controlled their own media rights.

More Sports News

The Beginning

After the 1984 ruling the CFA negotiated television contracts with ABC, ESPN, and TBS worth $21.2 million dollars. Non-CFA schools of the Big 10, Pac-10, ACC, Army, Navy and Miami went over to CBS for a combined $11.5 million ($8 million for the Pac-10/Big 10 and $3 million for the rest). The deals continued to get bigger and bigger and in 1991 Notre Dame left the CFA for their own 5-year, $38 million deal with NBC. 1996 saw the SEC move over to CBS with a 5-year, $85 million deal in addition to an ESPN deal worth $30 million. Not to be outdone, in 1995 the Big Ten signed a 10-year deal worth $100 million with ESPN. The Pac-10 had deals with ABC/ESPN and FOX Sports Net worth $32.2 million per year from 1997-2006. The Big 12 had two contracts: One with ABC that was for 8 years and worth $122.7 million and one with FOX Sports for 5 years and worth $42.5 million. The ACC started with a 5-year, $80-million-dollar deal with ABC, ESPN, and Jefferson Pilot. The arms race in college football had started and was showing no signs of slowing down.

Current Terms

The popularity of college football continued to rise, and the television deals continued to get larger and larger as a result. The various waves of conference realignment are directly tied to how much money can each conference get from the various networks. Since live sports are the only true non-DVR or non-delayed programming available, the conferences can get top dollar for their content. As of the 2024 season, the Big Ten has a deal that runs through the 2029-30 academic year and will pay out $1.15 billion per year – currently the largest of any conference. The SEC will receive $710 million from ABC/ESPN, while the Big 12 ($383 million) and ACC ($372 million) lag behind the “Power 2.”

Another Lawsuit

In 2009, Ed O’Bannon, a starter on the UCLA 1995 National Championship basketball team, filed a lawsuit against the NCAA alleging a breach of antitrust laws after seeing a player that strongly resembled his height, weight, left-handed shot, and position on EA Sports NCAA Basketball ’09 video game. The O’Bannon suit alleged that the NCAA licensed his Name, Image, and Likeness to EA Sports without his approval and without compensation. In 2019 Judge Claudia Wilken ruled in favor of O’Bannon and other plaintiffs that had been added to the class action lawsuit against the NCAA. After losing again on appeal, in 2021 the NCAA changed its rules to allow athletes to enter into sponsorship and endorsement agreements and allowed athletes to use agents to manage their business agreements.

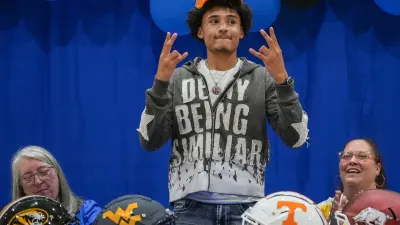

NIL, Collectives, and the Wild West

Almost as soon as the NCAA announced changes to the NIL rules, “collectives” began to pop up at various schools. These entities – who were not supposed to be affiliated with their respective schools – were soon offering obscene amounts of money to high school players under the guise of NIL agreements. Some would argue that these collectives are bringing into the light what has been done under the table for years. There is certainly truth to that statement. The “bag men of the SEC” stories are legendary, players having no-show jobs and still getting paid at Oklahoma and Texas are well known, and the original NIL school SMU is just now recovering from having the death penalty imposed on it in the mid 1980s. However, the amounts of money then and what is being thrown around now are completely different. In 2022 Ohio State head coach Ryan Day told boosters that the Buckeyes roster would cost around $13 million dollars that season.

The transfer portal, unlimited transfers, player retention and roster poaching have turned roster management into the Wild West. Players are going to their coaches and asking for bigger NIL deals to stay at their current school while other schools are using third parties to “encourage” players to jump into the portal for a larger payday at their new school.

Where Does College Football Go from Here?

Everyone is waiting for Congress to pass some sort of legislation to put guardrails on NIL and potential direct payment to the players from the schools. The conferences themselves won’t put any guidelines out because it immediately puts them at a recruiting disadvantage to conferences that don’t have the same limitations. The NCAA is a toothless tiger that needs to be replaced by a new organization that works in the best interest of the athletes and the schools.

What will most likely happen is that the “Power 4” or some variation of those schools will break off and form their own football-only league complete with a salary cap, playoffs, and a championship game sometime in late January. I might be wrong, but that sounds very much like a league that already exists and plays on Sunday.

Unfortunately, there are no easy answers and there are likely to be more growing pains along the way.